2025 STORYLINES: The March Wildfires

Nine months after Stillwater's historic wildfires, questions about preparedness and recovery remain

Nine months after Stillwater's historic wildfires, questions about preparedness and recovery remain

We could smell the fire before we could see the smoke.

It was Friday morning, March 14, 2025, and I was helping Trey Nixon livestream The Mid South 50k finish line. Spectators, event staff, and cyclists lined 7th Ave. downtown to cheer on the finishers.

The late winter event is known for cool, wet, and sometimes extremely muddy conditions but this weekend was shaping up to be a dry yet very windy affair. About an hour after the 50k runners had left the startline the wind gusts began to pick up.

According to Weather Underground data by noon wind speeds were averaging 36 mph with gusts up to 60 mph in Stillwater turning 7th Ave turns into a wind tunnel, blowing dust, dirt, and tents around. That morning, the gusts were relentless.

The Mid South finish line before and during the crisis. Left: The livestream monitor captures the 50K running event on 7th Avenue. Right: Event manager Crystal Wintle runs to help as high winds blow tent covers off downtown Stillwater on March 14, 2025. – Photos by Chris Peters

According the Stillwater Fire Department the fires had begun around 1:20 p.m. with winds gusting at 70 mph. Humidity had dropped to 12 percent.

By 1:30 p.m. dozens of runners had gotten their mandatory finish line hug from event promoter and director of stoke, Bobby Wintle. Runners talked about being sandblasted by wind and dirt on the course.

Around 2 p.m. I began to notice what smelled like a campfire.

By 3 p.m. the National Weather Service issued a fire warning for Stillwater.

3:00 - A dangerous wildfire is just southeast of Lake Carl Blackwell and moving rapidly northeast. If you live west of Stillwater, be ready to evacuate immediately. pic.twitter.com/a9OAHO2Imu

— NWS Norman (@NWSNorman) March 14, 2025

124 out of 142 runners were able to finish while event officials starting pulling runners and aid stations crews off the course. The media crew downtown began sharing information about intense smoke on course but didn't know the source. We just knew something was on fire.

Then Trey got a call.

Trey, whose family has property in the warning area southwest of Stillwater, immediately turned off the stream, left his equipment, and headed toward his family's ranch that also served as an aid station for runners on course.

When Trey arrived, flames were approaching his family's home. Their well water pump had lost electricity due to a power outage but with water from aid station he was able to save the structures on property from severe damage.

I had been buzzing just two days earlier from breaking the news that Google was behind the data center project everyone had been speculating about. Now I was racing home to prepare for possible evacuation with my family while smoke darkened the sky.

Fly Home for the Holidays 🎄✈️

There’s nothing like the holidays in Stillwater—familiar streets, friendly faces, and traditions that feel like home.Visit Stillwater is helping make the trip back easier with airfare giveaways and holiday travel incentives. Because the best gift this season is being home.

Shortly after I got home, friends who'd come from Michigan to ride in Saturday's bicycle event told us their hotel off Highway 51 was being evacuated and asked if they could stay with us. Of course, we said yes.

We sat in front of the TV flipping between different OKC TV station livestreams and refreshing Facebook for any updates that could provide some insight into the situation. We were also waiting on the status of Saturday's Mid South events.

Then late Friday night, we saw a video post with race director Bobby Wintle sitting on a shop stool at District Bicycles, announcing the event was officially canceled. The exhaustion and heartbreak in his face said everything.

The Mid South is not only an attractant for endurance athletes, adventurers, and musicians—the event purposely brings in professional storytellers. Over a dozen photographers and videographers descend on the route, capturing a multitude of perspectives of the event. That can be the high-speed action of pro cyclists ripping down a red dirt road or the shoes of a runner crushing gravel one foot at a time.

Many turned their camera lenses toward the new story forming around them. Photographers who'd been positioned to capture runners on course and crossing finish lines suddenly found themselves documenting a sky filled with dirty orange smoke.

The Mid South Creative Director Josh McCullock and the crew at Ovrlnd.Studio had come to document an endurance celebration. "I was shocked how fast the event went from full activation to an abrupt evacuation effort," McCullock would later say. "Our cameras kept rolling, even as our crew members assisted with evacuations."

Nick Oxford was in Oklahoma City when he heard the news. A freelance photojournalist who'd won a Pulitzer Prize as part of a New York Times team in 2022, Oxford knew something about red flag fire warnings. With alerts across the state, he'd already prepared his safety gear.

When news broke about a growing wildfire heading toward Stillwater neighborhoods, Oxford started driving north.

He didn't have to go far after turning south on Range Road from Highway 51 to see a neighborhood with residents desperately trying to protect their homes with water hoses. Oxford also witnessed Stillwater Fire Department doing their best to save any home they could. But the winds were too strong. Hot embers from one engulfed home would travel to ignite the next, multiple doors away.

Oxford has covered wildfires before as a photojournalist, but he had never experienced a fire that spread so quickly from home to home. He's undergone extensive training to safely insert himself into hostile environments—including emergency first aid and FEMA's wildland urban interface fire course.

A residence burns in Stillwater, Oklahoma. More photos of the week: https://t.co/7iv7TehuzG 📷 @NickOxfordPhoto pic.twitter.com/Bx6OZWLhoY

— Reuters Pictures (@reuterspictures) March 23, 2025

"Even putting out a lawn sprinkler could help during a red flag day," Oxford would later recommend.

The images he captured that day showed the stark reality: entire neighborhoods consumed, firefighters overwhelmed, residents watching their lives burn.

Local videographer Gabe Gudgel flew his drone Sunday March 16, 2025 to document the damage to the Hidden Oaks and Nottingham neighborhoods from above.

I woke up Saturday and saw the City was hosting a press conference at 11 a.m. That's where I heard Fire Chief Terry Essary try to explain the unexplainable.

"To be honest with you, seeing your community on fire is a very unsettling thing and it's something a fire chief never wants to experience," Essary said during the press conference.

The statistics were staggering: more than 50 homes and structures destroyed or damaged in those first reports, though the number would eventually climb to 98 homes destroyed and 123 others impacted. The fire burned 26,301 acres from McElroy to 80th Avenue and from Highway 86 to Western Avenue. The Stillwater Fire Department received approximately 300 calls for service in a 12-hour period—equivalent to what they'd normally encounter in 30 days. They faced the volume of large structure fires that would typically occur over eight years.

Mayor Will Joyce issued a formal proclamation declaring a state of emergency. City Manager Brady Moore visited the affected areas that morning.

"Just driving through the scenes this morning and seeing some very close friends standing at the end of their driveways wondering what's next," Moore said.

No lives were lost. Five firefighters were treated and released. In a disaster of this magnitude, that alone felt like a miracle.

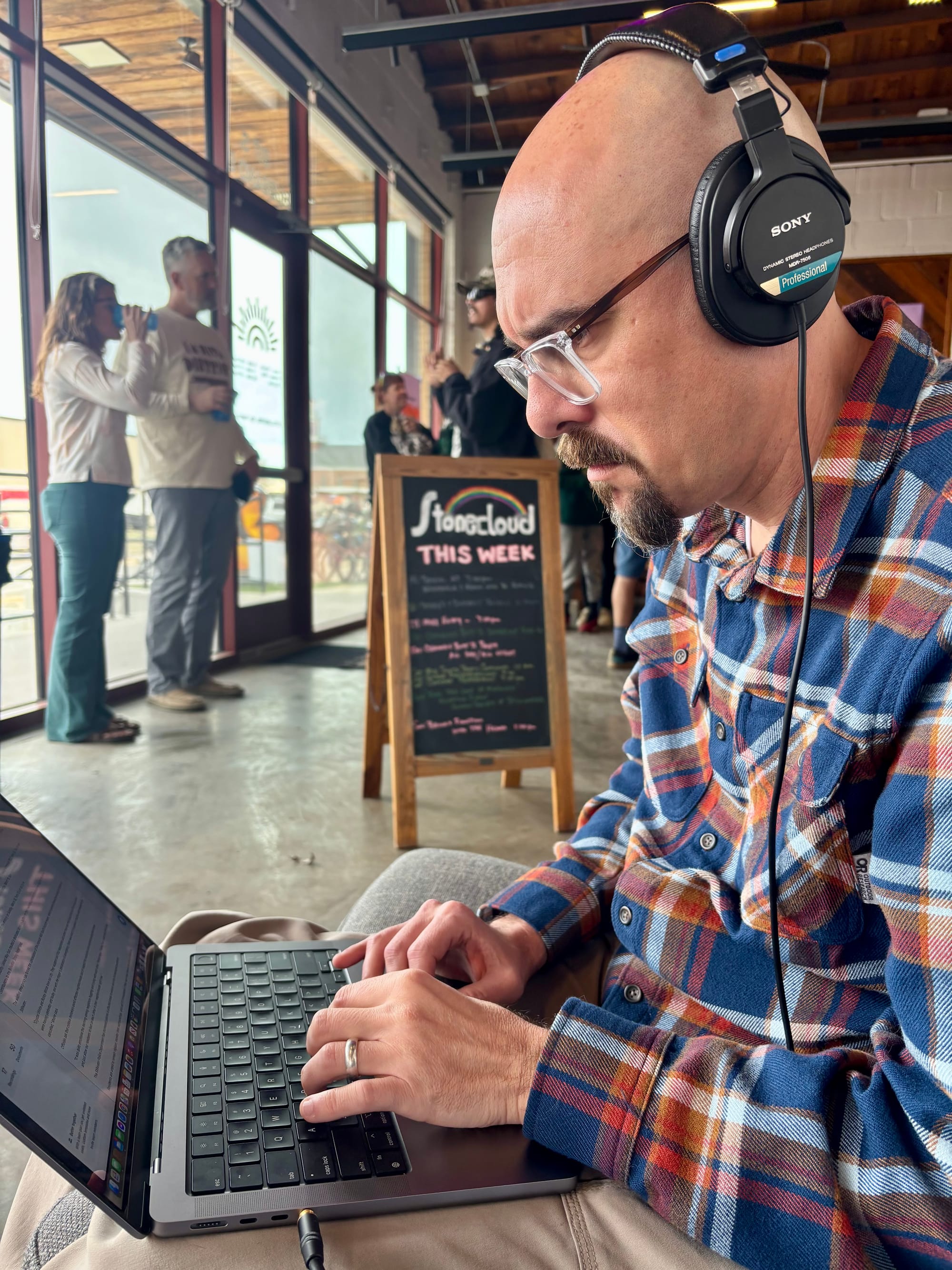

After the press conference, I went straight to Stonecloud Brewery to join Kara and our friends. Even though Saturday's events were canceled, hundreds of people were still in town. Multiple artists were there to perform. Stonecloud became the de facto Mid South hangout.

I busted out my laptop and headphones to immediately work on turning around a story from the press conference. I needed to get something published while people were still looking for information.

On March 19, five days after the fires, I got a text from friends. Carolyn West Meyer and Kel Pickens had lost everything.

I'd known Carolyn and Kel for years. We'd worked together on the KIDS Radio Show podcast, and I'd been to their home a few times before. So when I arrived at their property in the Nottingham neighborhood, watching Stillwater Multi-Jurisdictional Special Operations Team members carefully sift through ash and rubble, I had some familiarity with where things had been.

Walking through their destroyed home was surreal.

What struck me immediately was how Carolyn and Kel maintained their sense of humor despite standing in the remains of their home. "I would always say to Kel around the house, this place is so cluttered. I just hate clutter," Carolyn told me, with an actual smile on her face. "Well, that took care of the clutter."

I'm so honored they trusted me and let me video them exploring the ash and rubble of what was left of their possessions.

At 75 and 72 years old they'd lost a 1975 Porsche 911 S, high-end road bicycles, a collection of reel-to-reel recordings from radio shows they'd produced decades ago. Even a "fireproof" safe box containing $5,000 in twenty-dollar bills failed, leaving only charred remains.

I knew the burnt cash was a sight to see. I posted a video clip of them showing those burnt stacks of twenties on Facebook and Instagram. It went viral—1.3 million views, over 900 comments.

But the real story wasn't the cash. It was how they evacuated. Carolyn was at a hair appointment when her hairdresser looked at her phone and said, "What are you doing? You're supposed to be evacuating Nottingham." Kel was at a massage appointment, completely unaware. They scrambled to save what they could—computers, their cat Mandy, their dog Beau.

Unable to sleep that night, they drove to their property at 1:30 a.m. to discover everything gone.

"We just cried for a while," Carolyn said. "It was just surreal."

What happened next revealed the true character of Stillwater. A stranger from Ponca City stuffed bills into their hands at a pharmacy. The Hideaway gave them a significant discount. A coffee shop employee gave them free coffee. Friends offered accommodations across the country.

"We will rebuild," Carolyn said. "I like to say we're gonna rise from the ashes."

Their story, which I published on March 19, captured so much of what made this disaster both devastating and somehow bearable.

The phrase "Stillwater Strong" didn't need to be invented in March 2025. We'd already lived through it.

Ten years earlier, after the Oklahoma State University homecoming parade tragedy in 2015, the community had coined the term as shorthand for how we respond to crisis—not with hand-wringing or blame, but with action. When the fires hit, local leaders didn't need to debate what to do. They picked up that same spirit and ran with it.

Vice Mayor Amy Dzialowski coordinated with the United Way of Payne County within hours. The Stillwater Armory became a distribution center. Email addresses were set up for people needing help. Drop-off times were scheduled for donations.

It would have been more surprising if someone hadn't stepped up. Helping each other is just our default setting.

By early July, the Stillwater Strong Relief Fund had raised over $545,000 from more than 1,500 donors. That number still stuns me—not because it's high, but because it represents 1,500 individual decisions to help neighbors recover from disaster.

Three days after the fires, I was in a Payne County Commissioners meeting when Pierce Taylor, Director of Payne County Emergency Management, revealed a critical vulnerability.

"With the past fires that have happened over the week, this new radio system for in-county communication would have made a night and day difference," Taylor said. "There were issues with Yale's radio system going down and then at one point the tri-county radio system had a loss of communication as well."

The county had been working on a new emergency radio system for two years, funded by ARPA money. As of that March meeting, they hoped it would be operational by Christmas 2025.

As of late December 2025—nine months later—the county-wide radio system is about 90 percent complete but still not operational.

Pierce Taylor explained the delay: some equipment arrived not working properly and had to be reordered, and the county is waiting on network circuits that will allow signals to transmit from towers to dispatch centers through the system's redundant network.

"I'm hoping they give me a timeline sometime soon," Taylor told me in a late December interview. He couldn't provide a specific completion date—the installers haven't given him one yet.

The county continues operating on the old VHF system for day-to-day operations. But Taylor remains confident the new system will make a significant difference when it's finally operational.

"I do truly think this will make a huge difference to everything from the day-to-day responses to those one-in-a-lifetime fires, like the March fires," Taylor said. "There's so much redundancy built into it, and it's really a system that's built for large amounts of traffic."

One key improvement: unlike the current VHF system where you don't know if your transmission is getting through, the new radios will alert users if they can't hit an antenna. During the fires, not knowing whether communications were being received added to the chaos.

Left: Payne County Emergency Management Director Pierce Taylor during a commissioners meeting. Right: County Assessor Jason Gomez speaks at a budget board meeting, Sept. 8, 2025. – Photos by Chris Peters

A month later, County Assessor Jason Gomez delivered another sobering reality: "These values of millions of dollars in net assessment is coming off of the tax roll for 2025."

Due to Oklahoma statutes protecting disaster victims, even rebuilt properties would have their taxable values capped at pre-disaster levels for five years. The financial impact will ripple through county and school budgets for years.

The meeting also revealed that county road equipment wasn't designed for firefighting. When Commissioner Rhonda Markum raised concerns about rural residents who couldn't get help, Taylor explained the reality: "The dozers that the districts have are built different. They're built to grade roads."

Sheriff Joe Harper added: "We just ran out of fire apparatus for response. We couldn't get mutual aid from anybody because everybody else was burning up too."

On July 8, nearly four months after the fires, the Stillwater City Council did something that exemplified what I think local government should do.

They unanimously voted to waive approximately $75,000 in rural fire bills for property owners affected by the wildfire. The waiver applied to 24 billable incidents out of 89 total fire department responses during March 14-19.

"As we watch our community recover from the March 14th wildfires, this is a really important opportunity for the city to step in and provide some relief," Vice Mayor Dzialowski said. "It's quite clear as you talk to families and people out in the community that have been impacted by these wildfires, that the unmet needs in our community are still quite large."

The dollar amount mattered, but the gesture mattered more. The city was saying: we see you, we're with you, and we're not going to make this harder than it already is. They helped when and how they could. They were sensitive to the acute situation. And they ran it by us first, through the public process.

That's what I want from local government.

While I was covering policy responses and budget implications, Josh McCullock and his crew were turning their footage into something more lasting.

On May 8, I wrote about the documentary trailer McCullock released: "What's Left is Love."

The film captured stories like Bobby Wintle, sitting on that shop stool making the hardest decision of his life, canceling the event while grappling with loss in the community he loves. Lieutenant Leah Storm from OSU Police, transitioning from race support to conducting evacuations. Ted King and Chase Wark raising $11,000 by attempting a fastest known time on the 300-mile Mega Mid South route and so many more.

When I talked to Josh about the project, he explained why he postponed the initial screening. He'd thought he had a complete story, but in talking to victims, he realized their stories were just beginning. He didn't want to make a disaster film. He wanted to document resilience and recovery—and those stories need time to unfold properly.

The sensitivity in that decision impressed me. He recognized the emotional impact that weekend had on victims, the community, and first responders. Some stories can't be rushed.

The wildfire story isn't over. It's ongoing, evolving, revealing itself in budget meetings and SBA applications and documentary footage and rebuilt homes.

In 2026, I'll be watching for whether Gomez's predictions about tax revenue come true and how the county and schools adapt. How families like Carolyn and Kel have successfully rebuilt. How the emergency radio system proves its worth during the next crisis. When"What's Left is Love" screens for the community.

Since the fires, both the county and city have expanded their emergency notification capabilities. Payne County is working toward implementing a Rave Alert mass notification system similar to what Stillwater already uses, giving residents more options beyond Facebook for emergency updates.

While creating this storyline, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own level of weather awareness. Since I visit this website daily, I thought it would be a great place to check the current weather conditions and enhance my weather knowledge. Fortunately, Oklahoma Mesonet offers resources for news websites to embed their live weather widgets. With these resources, I’ve created a Live Local Weather page on The Stillwegian that provides real-time information on fire danger conditions, wind speeds, humidity levels, and weather forecasts. This page is freely accessible to the public.

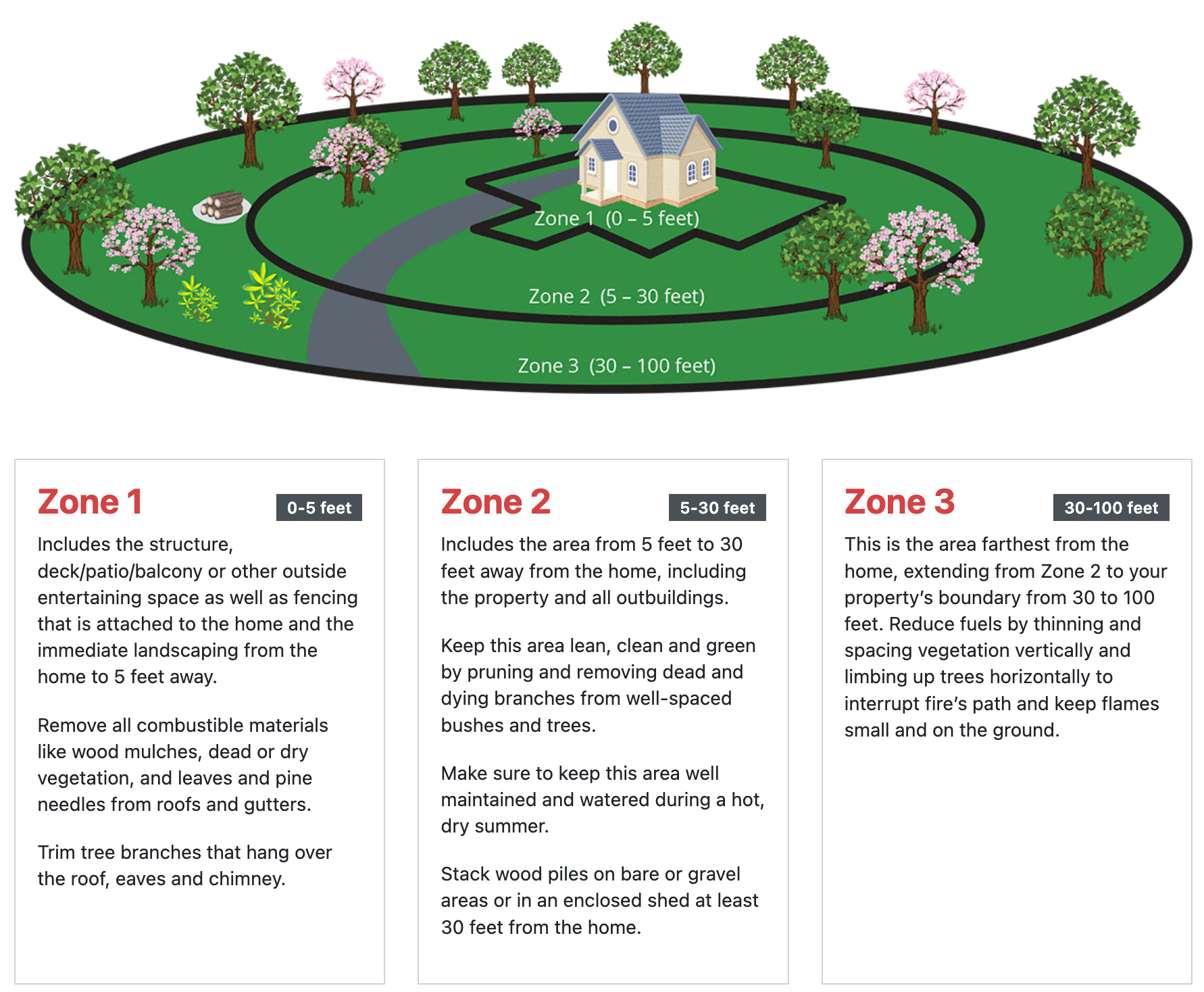

OSU Extension has resources for prevention, emergency planning, and evacuation. Consumer horticulturist David Hillock suggests evaluating property in zones, keeping roofs and gutters clean, clearing leaves and dry vegetation at least five feet from houses, and ensuring vents are properly screened against embers.

But preparation isn't just individual—it's communal. If your neighbor's property catches fire, your risk increases dramatically.